A new law aims to improve “cultural competency, cultural humility, and antiracism” among Vermont’s mental health professionals. It also intends to find ways to expand the mental health workforce by identifying barriers for aspirants in underrepresented groups.

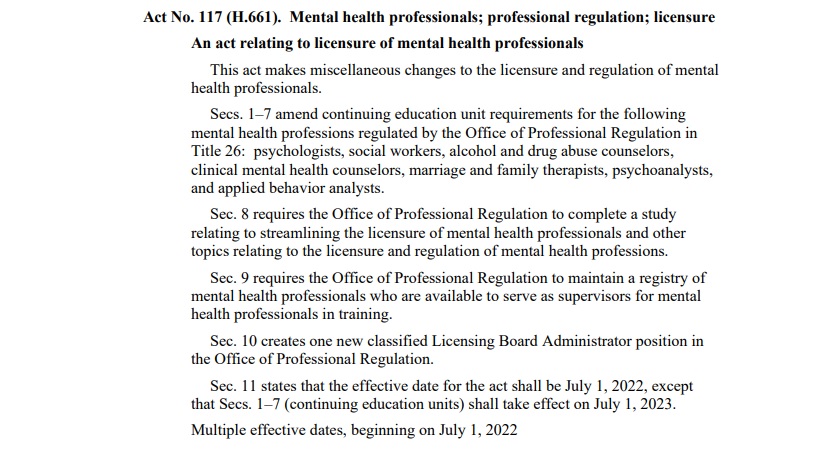

H. 661 amends the criteria for the biennial licensure renewal for psychologists, social workers, alcohol and drug abuse counselors, clinical mental health counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychoanalysts, and behavior analysts. Notably, it adds a requirement for “one or more continuing education units in the area of systematic oppression and anti-oppressive practice.”

Rep. Tanya Vyhovsky, who introduced the legislation, is a school social worker who previously served as the program director for the Pathways Vermont Support Line. “It’s not that we think mental health practitioners are necessarily more biased than another healthcare profession, but due to the nature of the work that we’re doing, it’s really important to think about how we sit with people when they’re really struggling,” she said.

The law does not increase the total number of continuing education units that mental health professionals must complete in order to continue to practice. On the contrary, it seeks in two ways to ease their burden of relicensure: by sanctioning synchronous virtual training (in addition to in-person classes) and by eliminating the necessity for dual licensees to undertake continuing education twice. Instead, one set of completed courses can count toward two or more licenses.

As introduced in January, H. 661 sought to compel mental health professionals to study “diversity, equity, and inclusion” within this process. By late March, three such units of continuing education had become “one or more.” With the encouragement of the Vermont Center for Independent Living (VCIL), the focus of these units also had shifted to “systematic oppression.”

“Making sure the educational opportunities are there that are not going to cause additional harm is really important,” VCIL Executive Director Sarah Launderville testified. “There are training modules that have been used in the past that cause additional oppression to marginalized communities.”

With H. 661 referred to the House Committee on Government Operations, members of the House Committee on Health Care nevertheless proposed a revision to accommodate work already in process as a result of their own Act 33 (2021), whose Health Equity Advisory Commission will submit a report on training and licensure in October. In order to allow for the use of the commission’s recommendations, the final version of H. 661 postponed the effective date for the new continuing education requirements to July 1, 2023.

The rest of the law will go into effect this summer, including a mandate for the Office of Professional Regulation (OPR) to conduct a study that will locate obstacles to entry into the mental health field for “individuals who are Black, Indigenous, or Persons of Color (BIPOC), refugees and new Americans, individuals with low income, and those with lived mental health and substance use experience.”

Xusana Davis, Vermont’s Executive Director of Racial Equity, spoke to legislators about prejudices in hiring: “If you’ve ever heard discussions, particularly in a human resources context, about things like ‘culture fit,’ I would strongly encourage us to think about ‘culture add,’ not ‘culture fit,’ because, oftentimes, what we’re saying when we say ‘culture fit’ is, ‘Do you fit in? Can you replicate the practices and behaviors and interpersonal styles that we already have?’”

“What that means,” she continued, “is that candidates who are from cultures that may be different than ours end up getting shut out, because we see them as other or different and therefore somehow less able to interact with people in the way that we’re accustomed to. But we have to step back and ask ourselves, ‘Is the way that we’re accustomed to interacting with people the only way?’”

VCIL, along with the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, the LGBTQ nonprofit Outright Vermont, and the refugee organization AALV, will assist OPR in this endeavor. Amid a widely reported labor shortage in the mental health field, OPR will also create a “registry of mental health professionals who are available to serve as supervisors for mental health professionals in training,” and it will look at ways of potentially “streamlining the licensure of mental health professionals.”

“We have a licensure issue in the state, in terms of how long it takes us to get mental health providers licensed,” OPR Director Lauren Hibbert commented. “The statutes are very complicated – well-intentioned but very complicated – and our rules are circuitous and very confusing. They’re very hard for an external applicant to navigate.”

As a result, the “one staff person for all mental health licensing in this state” receives, by Hibbert’s account, 700 emails in an average week. H. 661 adds one more Licensing Board Administrator to OPR’s staff to help with the workload.