On Jan. 15, the Vermont General Assembly learned that the Department of Mental Health (DMH) recorded 50 incidences of court-approved involuntary non-emergency psychiatric medication in Vermont hospitals in fiscal year 2021 (FY21), which began on July 1, 2020, and ended on June 30, 2021. This represented a small decrease since FY20, when DMH recorded 57 incidences.

Vermont’s Act 114 governs the use of involuntary non-emergency psychiatric medication, forcing hospitals to request that the Attorney General’s DMH office file a petition to the Family Division of the Superior Court for permission to make use of the practice. An independent reviewer, Flint Springs Associates (FSA), compiles an annual assessment of Act 114’s implementation.

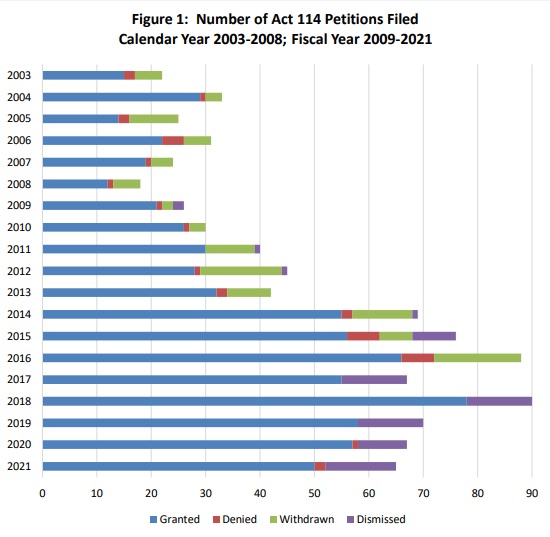

Hospitals reportedly sought a total of 65 petitions (on behalf of 56 patients) in FY21, three fewer than in FY20. Judges granted 77% of these, compared to 84% previously. Petitions peaked in FY18 at 90 and, year by year, have slowly declined since.

According to the report, the Commissioner of Mental Health has authorized five hospitals to administer medication under Act 114. All of them, except Central Vermont Medical Center, did so in FY21: the Brattleboro Retreat, Rutland Regional Medical Center, UVM Medical Center, and the Vermont Psychiatric Care Hospital.

As in earlier years, FSA contacted Vermont Legal Aid’s Mental Health Law Project (MHLP), which represents “the vast majority of patients” in Act 114 court hearings, and Vermont Psychiatric Survivors (VPS), whose Patient Representatives advocate for individuals in psychiatric facilities across the state. Owing to COVID-19, however, FSA found that VPS staff “had not had a presence in the hospitals that administer Act 114 medication orders” in FY21.

“Over the years in which this study has been conducted, MHLP has pointed to the absence of meaningful community resources for people with mental illness,” the report observes. “As a result, they believe that hospitalization and forced medication are being imposed on people who, given a wider range of community alternatives for treatment, would not need hospitalization.”

This time, MHLP also opined that the hospitals’ use of Clozaril – an antipsychotic that “requires regular blood draws” – may be illegal: “While the medication is regarded as very effective in its alleviation of certain symptoms, it can cause one’s white cell count to crash, making a person unable to resist infections. MHLP thinks that the involuntary blood draws are not authorized by the statute and, as currently conducted, are highly intrusive.”

FSA also interviewed four recipients of Act 114 medication in FY21.

“Responses were mixed to the questions regarding how the Act 114 protocols were followed, whether they felt they had some control, [and] how they felt they were treated, supported, and respected during the experience,” the report notes. “The only point on which respondents agreed was their belief that the state did not make the right decision in ordering Act 114 medication for them.”

Upon the filing of Act 114 petitions, hospitals must inform their patients about the resultant court hearing and any subsequent court order. By the patients’ accounts, that doesn’t always happen.

“Only one individual said that s/he was told the date and time of the court hearing, while two other respondents said they were given no information about the hearing and one person could not remember what, if any information s/he received,” FSA reported. “None of the four attended the court hearing and only one individual said that both the doctor and lawyer informed him/her about the hearing outcome.”

By DMH protocol, hospitals also must make emotional support services available to patients following Act 114 procedures, according to FSA, but the patients interviewed in the report allegedly did not receive these offers.

One patient, a self-professed “deep skeptic of the medical model of mental illness,” explained their resistance to taking the prescribed medication voluntarily: “The strategy of modern psychiatry is to medicate emotion and agitation rather than address the problem in therapy sessions. People are still upset, but now they are sedated. And it’s harmful physically – after 20 years of taking those drugs, I was diagnosed with diabetes.”

Additional testimony blamed psychiatric facilities that “aren’t structured for long-term care” for attempting to take pharmacological shortcuts: “Time is a serious component in recovery. Your mind needs time to recover. The goal these days is to get people out as quickly as possible and that is how they are rationalizing these forced medications.”

Per FSA, Act 114 patients spent an average of 91 days under hospitalization in FY21. Lengths of stay for this group have declined significantly over the past 15 years, from an average of 297 days in FY06. Hospitals have begun to seek Act 114 petitions sooner than they used to: 34 days after a patient’s admission on average in FY21, compared to 39 days in FY20. In FY06, the average was 129 days.

“Let me figure out my episode on my own terms at my own speed,” a patient urged. “If I’m in a hospital, then I should be able to retain control about what goes into my body.”

The sentiment was not universal. “In one instance,” FSA recounted, “a person reported s/he is now happy that the medications being taken work and have little side effects and gave kudos to the staff at the Brattleboro Retreat, who were credited with being kind and making it ‘a nice place to be involuntarily.’”