BENNINGTON – The state legislature budgeted $9.225 million in fiscal year 2024 for the construction of an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit at Southwestern Vermont Medical Center, indicating its approval of the project.

The Department of Mental Health told legislators that the plan was moving forward to develop a 12-bed unit. The recently completed feasibility study “suggests the need for more than 12” beds in addition to the existing 10 to 14 beds at the Brattleboro Retreat, DMH reported.

However, according to SVMC Director of Planning James Trimarchi, the final status of the proposal remains uncertain until the hospital Board of Directors decides whether to move forward, which is not expected to occur before August or September.

That would be a delay of three or more months from the original timeline, which he attributed to uncertainty surrounding the legislature’s appropriations bill.

The feasibility study – which Trimarchi said was still a draft – reported that “clinical experience, anecdotal information, and state reports indicate that a crisis exists in access” to adolescent inpatient care but that no “structured data is available to accurately calculate the number of additional beds needed in Vermont,” which “could be zero to 12.”

“The real answer is that we don’t know,” Trimarchi said.

DMH initially requested an allocation for the project in January during the annual budget adjustment, stressing a need to “reduce the number of youth waiting in an emergency department” and to serve “individuals who are currently denied admission at the Brattleboro Retreat due to medical needs that cannot be managed in a non-medical hospital setting.”

But legislators waited until spring, when SVMC had completed the initial feasibility study, to approve the funds.

The study identifies a former area for medical records within the hospital as a suitable site for the unit. The document’s schematic shows 12 bedrooms, as well as a dining room, two social rooms, a consult room, and a seclusion suite, as well as access to an outdoor area.

DMH had contracted SVMC to perform the feasibility study in October. The contract included a requirement to “obtain feedback on the design and operations from the local Designated Agency, mental health advocacy organization[s] such as Disability Rights Vermont and persons with lived experience.”

While SVMC maintains regular contact with United Counseling Service, Bennington County’s “designated agency” for mental health, it did not reach out to any other groups during the preparation of the feasibility study, Director of Planning James Trimarchi acknowledged.

“There has been no public input to the process at this point,” said Trimarchi, who characterized the feasibility study as a technical procedure carried out via spreadsheets and diagrams.

Trimarchi noted that SVMC’s Board of Directors hasn’t yet reviewed the results.

The Chair of the House Health Care Committee, Rep. Lori Houghton, appeared to believe the commitment to the site was more definite when she said on the House floor on May 12 that SVMC will be beginning the Certificate of Need process this summer to get approval for the project from the Green Mountain Care Board. Based on testimony by DMH to the committee earlier that week, “The intent by the Department of Mental Health… is for the beds to be placed at Southwestern Medical Center,” Houghton said.

In a timeline presentation to the committee, Commissioner Emily Hawes showed a graph from the SVMC feasibility report based upon Board approval by May and the Green Mountain Care Board application to be filed by June, which could not actually occur until after the SVMC approval.

Trimarchi indicated that the hospital would begin to survey advocates and community members after the Board approval in late summer. “We’re a long ways to ‘yes’ on this thing,” he observed. “So if we decide to proceed, the input from the public will be critical because that’s where we will share with them the block diagram and say, ‘Does this layout for individuals with lived experience make sense?’”

The feasibility contract ended on March 31. But Trimarchi emphasized in May that the study was “not technically done. It’s still in draft phase.”

“I haven’t received input from the Department of Mental Health yet,” he said. “If they come back and say, ‘Hey, we gotta share this with the disability rights group to have their input before we can close the book on it,’ then let’s do that.”

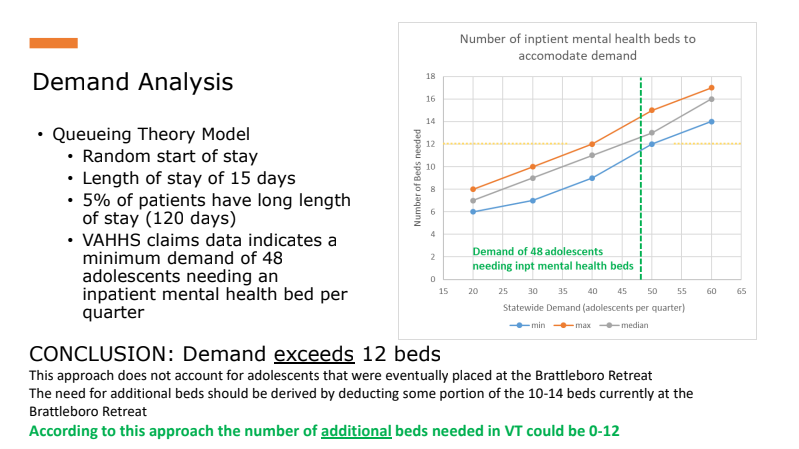

Part of the feasibility study was a “demand analysis,” which sought to quantify Vermont’s need for additional adolescent inpatient beds. One model used figures from Massachusetts, which has 38.4 beds per 100,000 kids. The same rate, transposed to Vermont, would yield a total of 18.5 youth beds.

Meanwhile, a “queuing theory model” – based on Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems data suggesting that 48 adolescents per quarter need inpatient care, with an average length of stay of 15 days – seemed to indicate that Vermont should have 12 or more youth beds.

Trimarchi views a model developed by the American Psychiatric Association in 2022 as the most accurate for calculating demand. He pointed to its consideration of “more than 40” factors, including the availability of community-based resources. But by his account, Vermont hasn’t yet aggregated all the information needed to use it.

And even if it did, that information could shift at any time. “Demand could change if, all of a sudden, there is an investment in equal resources dedicated to building out outpatient services,” Trimarchi posited. “I have very little sense that the calculation of demand can even be done sensibly.”

Still, for him, the need to “do something” remains apparent. The current thinking is, let’s build this 12-bed unit. If it eliminates the languishing in the emergency departments,” Trimarchi theorized, “then we know we’ve met demand. Until we do, we just gotta keep building these things.”

DMH Deputy Commissioner Allison Krompf told Counterpoint that she believes there is a consensus on the need for it. “I think the question mark still is, can an organization in this climate right now stand up a new wing of a facility, build staff? I would imagine any organization is not going to feel extremely definitive.”

Some legislators and advocates, however, have both questioned whether Bennington is the right place to do it.

“I’m just wondering if there are any other potential places that are further north,” Sen. Ginny Lyons said.

The SVMC feasibility study referred to the same question, asking, “Should new beds be created in southern Vermont since the current beds are also in southern Vermont at the Brattleboro Retreat (Vermonter’s expectation that care resources, particularly those funded by the state, are nearby and equitably located.)”

“Additional RFPs must be requested and ways found to help other institutions, such as the UVM Medical Center, meet the requirements of those RFPs,” NAMI-Vermont Board President Charles R. Siler urged in written testimony.

SVMC was the sole respondent to the second issuance of DMH’s request for proposals last year. The University of Vermont Medical Center initially threw its hat in the ring before withdrawing its plan on account of financial difficulties.

If the project moves forward at SVMC, it will aim for a launch date in December 2024. The projected annual cost of operations will exceed $7 million. It would likely require Medicaid to subsidize the costs as a result of private insurers’ tendency to under-reimburse inpatient psychiatric services. “The initial goal, although unlikely, would be to achieve reimbursement parity across payers,” the feasibility study said.