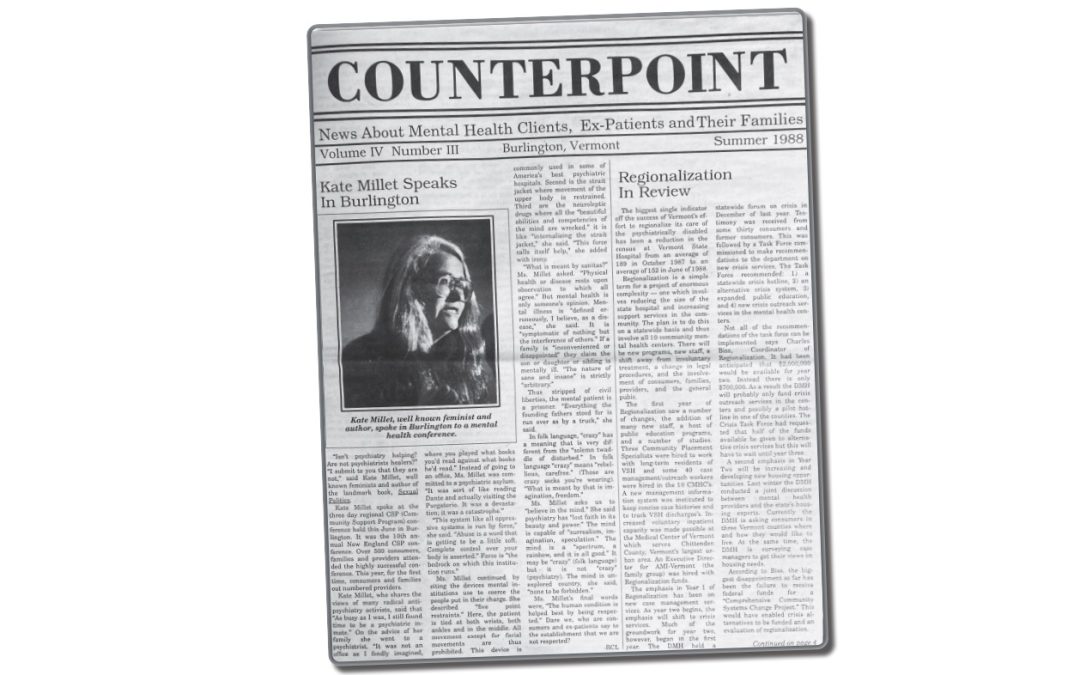

The summer issue of Counterpoint in 1988, 34 years ago, focused on a new plan called “regionalization” that had begun the year before to shift people who were being held at the Vermont State Hospital in Waterbury to living in their local communities with support services from mental health agencies. (Vermont Psychiatric Survivors has stored copies of Counterpoint beginning with 1988. It started publication in 1985, but there are no saved issues from the first three years.) The lead article featured a review of some of the early goals to reduce the number of patients being housed at VSH, which at the time was the only place where individuals were held against their will. What was happening then, and where do we stand now?

Average Number in Hospitals

1988 A goal of regionalization was to reduce the average daily number of patients being held against their will in the hospital. The average daily patient count at Vermont State Hospital was 152. This was down from 189 when the regionalization efforts began one year before. The all-time high had been 1,301 in 1954.

2022: The average daily patient count of individuals being held in hospitals against their will was 61. This included 36 at the Vermont Psychiatric Care Hospital and the other “Level 1” (highest security) hospital units in Rutland and Brattleboro that replaced VSH after it closed in 2011, and an additional 25 patients on other locked units at regional hospitals or the Brattleboro Retreat. (An average daily patient count is not the same as knowing how many different people are hospitalized each year, because if someone is there for a long time, it increases the average number of total days that there are people being held.)

Hospital Beds and Admissions

1988: The goal was to be able to close down the number of involuntary hospital beds that were, at the time, all at Vermont State Hospital. In the first year after the regionalization plan started, the Department of Mental Health reported that, “Contrary to what many had feared (that is, the creation of mini-state hospitals) no new involuntary units have been created.” (Counterpoint, Spring 1988.) The number of annual admissions in 1991 (the closest date with published data) was 329.

2022: Within 10 years, all regional hospitals with psychiatric units had begun admitting involuntary patients onto locked units. In 2002, the Retreat was the last to add patients being held against their will. In 2011, the last unlocked unit in the state became a locked unit. After Tropical Storm Irene closed the remaining 54 beds at the Vermont State Hospital in 2011, they were replaced by the new 25-bed Vermont Psychiatric Care Hospital, two “Level 1” units at regional hospitals (14 beds at the Brattleboro Retreat and 6 at Rutland Regional Medical Center) and seven locked residential beds, for a total of 52. In 2021, 12 new “Level 1” beds at the Brattleboro Retreat opened. An expansion in locked residential beds from 7 to 16 scheduled to open in 2023. Discussion is underway on whether a new facility for forensic patients (those with criminal system involvement) is needed. The number of admissions of involuntary patients increased between 1991 and 2021 from 329 to 573.

Crisis Services and Use of Peers

1988: A Task Force recommended these new programs: 1) a 24/7 statewide crisis hotline, 2) an alternative crisis system with a crisis center and “safe house” for 6-8 persons for stays up to 6 months, 3) new crisis outreach services in the mental health centers with peer available to stay with a person in crisis and individual crisis beds, (All three of these to be using consumer/ex-patient/peer staff), and 4) expanded public education on “what is a mental health crisis.”

2022: 1) The Pathways Support Line started statewide in 2013 and became 24/7 in 2020, 2) Community support centers exist in Burlington and Montpelier and Soteria House opened as an alternative residence with six beds in 2015; 3) Some community mental health centers (called “designated agencies”) have peer outreach staff. Several peers do outreach through Vermont Psychiatric Survivors. Alyssum hosts two peer-run crisis beds. The legislature has funded the start of an expansion of mobile outreach, with inclusion of peer staff, and 4) public education in recent years has included youth and adult suicide prevention.

Community Funding

1988: Funding for new crisis services was cut from an anticipated $2 million to $700,000 for the second year of the regionalization plan. Predictions were made about savings from closing hospital beds being earmarked for community services, but there were complaints about lack of money for community services.

2022: Funding for expansion of peer-led crisis centers was rejected by the legislature. Regular complaints are made about inadequate community funding to meet the original promise of closing Vermont State Hospital beds. There are no data reports for the ratio of money spent on hospital versus community services over the past 34 years.

And so, after 35 years of efforts, it might bring to mind the old French saying, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”: the more things change, the more they stay the same.