According to California’s Bridge Rail Foundation, more than 1,700 people have leapt to their death off the Golden Gate Bridge since its opening in 1937, making it “the world’s deadliest structure.” Fewer than 35 jumpers have survived the fall.

One of them is Kevin Hines, a San Francisco native who visited Manchester’s Burr and Burton Academy on Oct. 19 to talk about suicidality and recovery. United Counseling Service, Bennington County’s community mental health center, sponsored the free public event.

In a little over an hour, Hines narrated an autobiography beginning in what he called a “crack motel” in San Francisco’s notorious Tenderloin neighborhood. A clerk’s phone call to child services placed him, dirty and ill-nourished, into foster care, alongside his brother, who, amid what Hines characterized as continued neglect, would soon die from a bronchitis infection.

“Unlike my poor brother, I would get very, very lucky,” Hines said. Through adoption, he would find a stable, happy home at the age of nine months.

But that didn’t prevent him from facing mental health challenges in his teenage years. Hines described an experience of “paranoid delusions; hallucinations, auditory and visual; panic; highs, followed by depressive lows.”

“I thought that if I told anyone about what I was really going through, they would lock me up in a white-walled, padded room and throw away the key,” Hines said.

After Hines’s beloved high school drama teacher died by suicide, he began to consider it as an option for himself. Seven months later, the voices in his head had intensified, telling him that he “had to die, that it was inevitable.”

“Your brain is so very powerful,” Hines said. “And when it breaks, the rest of you will follow.”

On Sept. 25, 2000, a 19-year-old Hines rode a bus to the tip of the Presidio of San Francisco. He disembarked among a horde of tourists eager to glimpse “the most beautiful manmade structure ever created.”

“I sat there crying like a child, hoping, wishing, and praying that one person would see me, see my pain, and say something kind and compassionate,” Hines recollected. “‘Kid, is something wrong?’ ‘Can I help you?’ I would have told that person everything.”

Forty minutes later, Hines jumped.

“The millisecond my hands left that rail and my legs cleared it, I had an instantaneous regret for my actions and the absolute recognition that I had just made the greatest mistake of my life,” Hines recalled. “And it was likely too late.”

A passing driver used a carphone to call the Coast Guard, which rescued Hines. He credits a sea lion for keeping his badly injured body afloat until the boat’s arrival.

“I experience excruciating physical pain most of the day, every day,” Hines said. “But it doesn’t come close to the enemy I battle within.”

Hines’s extreme mental states didn’t stop after his suicide attempt. But he never attempted suicide again, and he no longer suffers in silence.

“The difference between me and people who die by suicide is that I do not stop saying ‘I need help now’ until someone is willing to answer the call,” Hines said.

On ten occasions, Hines entered inpatient care, sometimes involuntarily. At psychiatric hospitals, some doctors and nurses “genuinely care about what they’re doing,” but others, as Hines sees it, “are deadened to their job.”

“The way they treat us as second-class citizens,” Hines said, “the way they get angry when we recidivize back in the psych ward, and the way they look at us and call us out when we’re in pain is inappropriate.”

As a mental health and suicide prevention advocate, Hines believes in an intervention called “caring letters,” which he attributed to a San Francisco psychiatrist from the Department of Veterans Affairs. He emphasized the special power of written expressions of love and compassion from friends, family members, and peers.

“You give them a letter from three to five different people,” Hines said. “You mail it to them like it’s a present. They get it. They read it. They have it forever. When they feel hurt or in pain, they read it again and again and again.”

As an activist, Hines campaigned for the installation of a safety net on the Golden Gate Bridge, a $400 million project that contractors expect to finish this winter. In his view, the net isn’t just about catching jumpers.

“You show a community that you care by stopping an icon for suicide from being available,” he said. “Their minds change.”

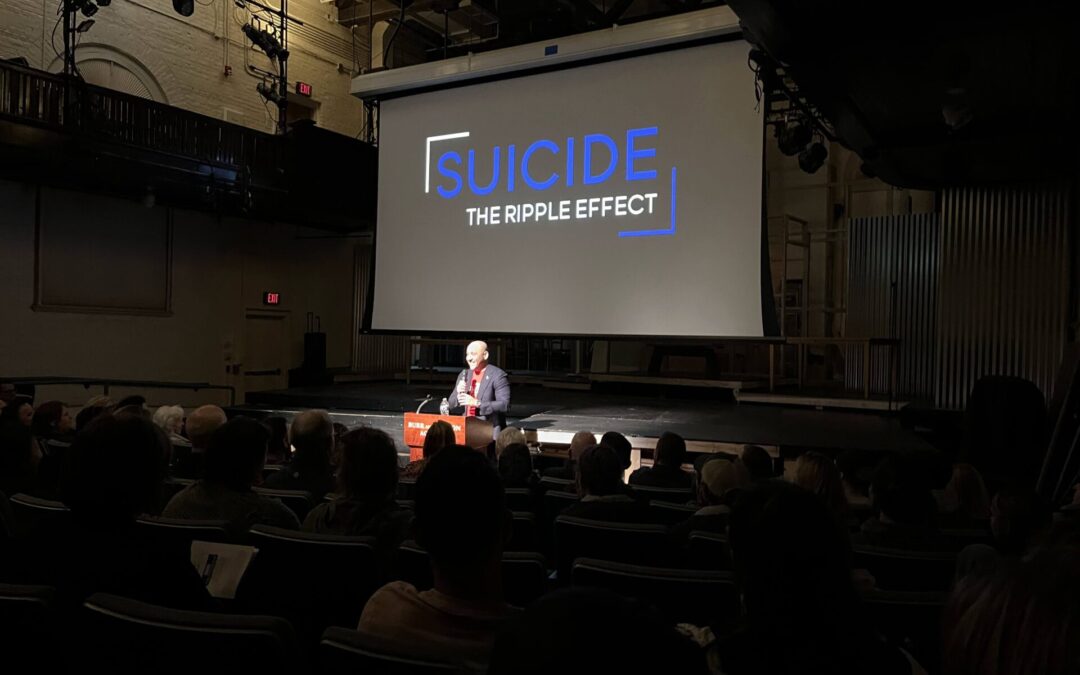

Today, Hines is an author and filmmaker who travels the country professionally as a motivational speaker. UCS held a screening of his documentary, Suicide: The Ripple Effect, on Oct. 4.

“I’ve seen Kevin a couple of times speaking in various places,” UCS Executive Director Lorna Mattern said. “Each time I was incredibly inspired by his story, his journey, his ability to share his hope.”

Hines tells audiences that their lives have value and that other people care about them and are ready to hear about their pain.

“Make a choice to never again silence your pain,” Hines said. “Why? Because your pain is valid. Your pain is worthy of my time and others’. And your pain matters simply because all of you do.”